Washington’s Pig Headed War

The killing of a pig nearly plunged the United States and Great Britain into war in 1859. Fortunately cooler heads prevailed.

Long before the San Juan Islands were a vacation destination, they were the focus of an international crisis ignited by an unlikely incident: The shooting of a pig in a potato patch. This was the famous Pig War of 1859, when military and naval forces of the United States and Great Britain almost came to blows in midsummer after the death of the Berkshire boar.

But in the end, not a single shot was fired. The nations opted for peace, an outcome that was commemorated more than 100 years later with the creation of San Juan Island National Historical Park. The issue, aside from mid-19th century notions of honor, was mainly about real estate.

After the Oregon Treaty of 1846 divided what was then known as the Oregon Country along the 49th parallel, the two nations were at loggerheads over the water boundary between Vancouver Island and the mainland. The coveted San Juan Archipelago lay in the middle. It didn’t help matters that U.S. settlers were vying for the land where the Hudson’s Bay Company raised more than 4,500 head of sheep, or that the British were uneasy about Americans observing ships transiting Victoria Harbor from San Juan’s southwestern shore, only seven miles across the Haro Strait.

Following a number of clashes over land and taxes that culminated in sheep rustling, the dispute boiled over on June 15, 1859. A failed American miner named Lyman Cutlar found a company pig rooting in his meager subsistence garden, and snapped. He seized his rifle and shot the intruder. This was the heinous act that nearly plunged the United States and Great Britain into war.

Cutlar was threatened with arrest by British authorities if he did not make fair restitution for the pig. He refused and went into hiding. This compelled Department of Oregon commander Brig. Gen. William S. Harney to dispatch Company D, 9th U.S. Infantry to San Juan Island in July, 1859 under the command of Capt. George E. Pickett.

This was a great tonic for Pickett, a Virginian and Mexican war veteran and the same officer who would one day lead his Confederate division at the Battle of Gettysburg. Bored with frontier court-martial boards that mainly tried drunks and deserters, he relished the opportunity to confront the British on San Juan. However, his enthusiasm overreached common sense. Despite being ordered by Harney to merely show the flag and protect U.S. citizens, Pickett posted a proclamation near his Griffin Bay camp. The third proviso read:

III. This being United States territory, no laws other than those of the United States, nor courts, except such as are held by virtue of said laws, will be recognized or allowed on this island.

An outraged Vancouver Island Gov. James Douglas volleyed by dispatching Capt. Geoffrey Phipps Hornby and the 31-gun steam frigate H.M.S. Tribune. Hornby was commanded to order Pickett off, and if the American did not comply, to refuse reinforcements or the erection of fortifications. British naval officers in Victoria warned Douglas that Hornby’s orders were too provocative. The Royal Navy’s mission, they stressed, was to maintain the peace, not start wars. But the governor countered by suggesting that Hornby land Royal Marines on the island equal in number to Pickett’s soldiers: 64. To lend weight to the proposition, two more warships dropped anchor in the bay.

Pickett refused to comply, and threatened to open fire should the marines attempt a landing. One pioneer account, written 40 years after the fact, offers a heroic portrayal of Pickett blustering, “We’ll make a Bunker Hill out of it!” But with 64 British naval guns pointed at his camp, he instead pleaded for reinforcements and lamented that his company was, “no more than a mouthful,” for the British. He was unaware that Hornby had no intention of forcing the issue, choosing instead to sit tight and await the return from sea of his superior, Rear Admiral R. Lambert Baynes. He was confident his inaction would be affirmed, and that is exactly what happened when the admiral learned of the incident a few days later.

“Tut, tut, no, no, the damned fools,” Baynes was said to have exclaim in his characteristic dry wit.

However, the crisis was far from over. On August 10, U.S. Army Lt. Col. Silas Casey arrived in the bay aboard the steamer Julia Barclay. This swift little sternwheeler ordinarily was a common and inoffensive sight on Puget Sound and the Northern Straits since her completion at Port Gamble the year before. But she had suddenly been “requisitioned” into a troop and munitions carrier to deliver more than 170 soldiers and three field pieces on South Beach just hours before depositing lumber and ammunition (and Casey) on the dock in full view of the by-now troubled Hornby.

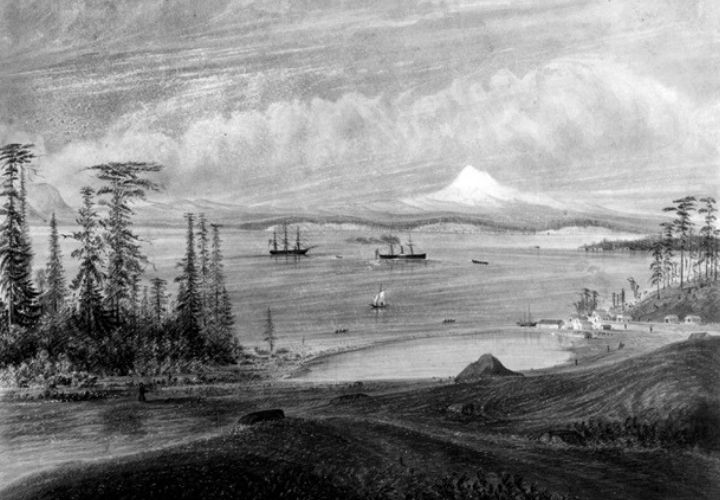

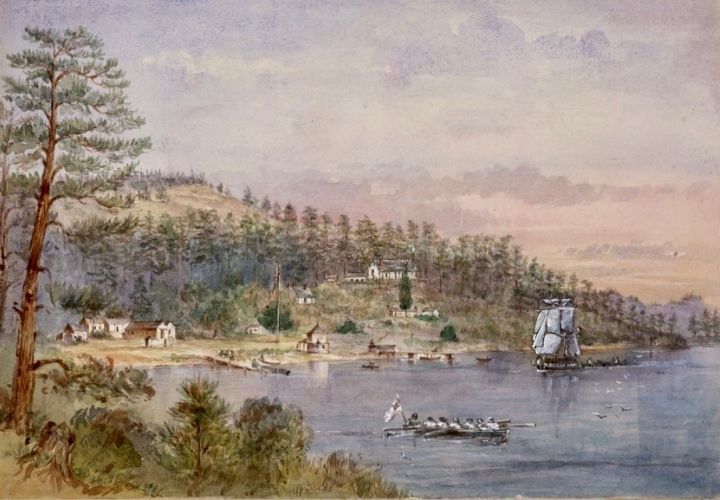

Old Town Lagoon on Griffin Bay, then and now. It was here that Capt. George E. Pickett and his 64 soldiers landed on July 27, 1859 prompting the British to respond with three warships. The town full of saloons and bordellos sprang up almost as soon as the soldiers landed. Photo provided by Beinecke Library, Yale University.

Four days later, Hornby was aghast to see eight, 32-pounder naval guns landed on the beach under his very nose. These were to be mounted in a redoubt overlooking the bay, and with a range of over a mile, could easily drive his ships from the harbor. He immediately sent a dispatch to Baynes asking if he should land the marines and spike the guns. Baynes’ reply was swift and firm: No. Hornby was to stand fast and await a diplomatic solution. A hand-carried telegraph and a messenger were already on the way to the East Coast.

When word reached Washington of the contretemps in September, officials from both nations agreed the situation called for a peacemaker on site. The obvious choice was U.S. Army commander Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott, who had calmed northern border crises in Maine and New York in the late 1830s. But by 1859 Scott was 73 years old, weighed nearly 400 pounds and was so immobilized by gout and dropsy he had to be hauled from shore to deck by crane.

Following a six-week voyage via a rail connection across Panama, Scott stopped first at Vancouver Barracks on the Columbia River. On learning that Pickett happened to be on post, he yanked both Pickett and Harney into his cabin and scolded them for their “little conquest.” He next relieved Harney of command and steamed on to the San Juan Islands, where it required only a week for Scott and Douglas to negotiate a stand down. The American force would be reduced to a company, and a British warship would remain on call.

By December, the two governments decided on a formal joint military occupation of the island. The Americans would remain on the southern end of the island, while the Royal Marines would eventually establish a camp 13 miles north on Westcott Creek, now Garrison Bay. The contingents were to be limited to 100 men each and no artillery.

Before leaving, Scott was more than happy to comply with a back-channel request by Douglas to deny Pickett’s company the honor of being the first official U.S. contingent. The governor was still seething over what he considered the Virginian’s provocative and “punctilious” behavior that summer. But believing he had only been following orders, Pickett was distressed by the slight. And his frustration grew when the ship returning his arms and stores to the mainland foundered in a December blizzard, and his men ended up spending the winter in a barn.

But Harney was not done. Restored to command on Scott’s departure, he ordered Pickett back to the island in April, when he then declared Scott’s agreement null and void. For this, he was quickly sent packing back east. Meanwhile, Pickett had learned the “arts of peace,” and established with his counterpart, Royal Marine Capt. George Bazalgette, a precedent for friendship and cooperation between the two garrisons that would continue through 1872. In fact, before the final decision, they would spend holidays together, marching en masse to the respective camps to engage in athletic contests (including log rolling), picnicking, drinking and horse racing.

Unfortunately, not everyone agreed with the diplomats concerning jurisdiction. Fueled by wishful thinking and misinformation campaigns, citizens and elected officials living in Washington Territory still believed the San Juans belonged to the United States alone. That was one issue. The other was the American distaste for martial law in any form, which dated to the occupation of Boston on the eve of the American Revolution by these same Redcoats.

British civilian authorities were not allowed on the island, so incidents between British subjects and Royal Marines were rare. Not so among the Americans. While most willingly accepted, and profited, from the tax-free status and frontier security of military camps, friction prevailed on the southern end of San Juan. There, a noisy minority based in San Juan Village was eager to smuggle or distill whiskey, purvey prostitutes and thumb their noses at the law in any guise. This created no end of frustration for U.S. military commanders, who finally resorted to evictions to maintain the peace.

Finally, on May 8, 1871, the Treaty of Washington was signed by the British and Americans and ratified by Congress the following month, proscribing that the dispute be settled through binding arbitration by a third power—Imperial Germany. Kaiser Wilhelm I selected a three-man commission that met in Geneva over the next year to determine whether the boundary should be Haro Strait or Rosario Strait. The commission voted two to one that the Haro Strait be designated the “southerly channel” dividing Vancouver Island from the mainland, as cited in the Treaty of 1846, because it touches Vancouver Island. The Rosario Strait does not. The ruling was issued on October 21, 1872.

English Camp today. Photo by Tomas Nevesely

A month later the Royal Marines marched peacefully out of English Camp leaving behind a tidy garrison replete with two docks, cisterns, gardens and 27 structures, four of which can be visited today in the National Park. The Americans immediately rushed in with a huge garrison flag to proclaim their “victory,” but arrived to find the 80-foot pole had been chopped down. In 1998 the United Kingdom replaced a replica pole, underscoring the peace and goodwill that has endured for a century and a half.

American Camp’s garrison departed two years later. Buildings that were not auctioned off became barns and farmhouses, and the prairies were cultivated for cereal crops. The one feature left untouched was the Redoubt, the earthwork engineered by Henry M. Robert for the placement of naval guns. This young officer would one day write “Robert’s Rules of Order.”

Today the Redoubt remains as sound and recognizable as it was the day the Army left, with a sprinkling of wildflowers every spring and 180-degree views of humpbacked islands and faraway peaks. More importantly, it remains the only tangible reminder of that intense summer of 1859, and the “war” in which the only casualty was a pig.

Continued Reading

Dive deeper into the drama of defining a Northwest boundary in Vouri’s lively, in-depth account. Get it today.

For Kids

Introduce your kiddos to this bit of past with Emma Bland Smith’s new children’s book exploring this historic event.