75 Years of Doing it Right

To most of us, flying is simply a fast and efficient way of getting from here to there. But it can be so much more. Accelerating across the water at the point of a sparkling vee of spray, lifting off to look down through big windows at the shining towers of a city beside a deepwater bay, skimming close over a jigsaw puzzle of islands and inlets, soaring around the ice-draped peaks and looming volcanoes that make up some of the most impressive mountains on the planet… Now that’s flying.

That this remarkable experience can be had by simply buying a ticket on Kenmore Air is due entirely to a single gust of wind which shortly before the outbreak of World War II flipped over a tiny, two-seat Aeronca floatplane on Seattle’s Lake Union. Seattle seaplane pioneer Lana Kurtzer salvaged the plane, stacked the pieces behind his shop and forgot about it until 1944 when a pair of young Navy Reserve aviation mechanics asked if he’d be willing to sell it.

The rebuilt Aeronca Model K in Bob Munro’s backyard, 1946.

Graduates of the Boeing School of Aeronautics, Reginald “Reg” Collins and Bob Munro were looking for an airplane rebuild project to hone their skills during their spare time. The fact the Aeronca was on floats was irrelevant since their post-war plan was to sell it and open a little aircraft repair shop. The agreed-on price was three hundred dollars and the restoration took a year.

In August, 1945 Collins and Munro began looking for a commercial garage to rent to house their repair shop. They found one on Green Lake Way just north of Lake Union, and then their longtime friend Jack Mines came home from flying anti-submarine planes in the Pacific and changed everything.

“Why don’t you start a business with it,” he suggested when he saw the assembled Aeronca in Munro’s backyard. “Offer flight instruction, charter flights, things like that.”

“Well, that’d be interesting,” said Collins. “ But neither one of us knows how to fly.”

“No, but I do,” said Mines, and he outlined his idea. He’d do the flying while Collins and Munro took care of the repair work. The two mechanics were skeptical but Mines’ enthusiasm finally won them over.

The first challenge was to find a place to fly the plane. Mines found it at the north end of Lake Washington, an abandoned shingle mill on a boggy mudflat in front of the town of Kenmore. The owner was willing to lease the property, so the Aeronca was disassembled, trucked to the site and reassembled. Its first flight was on March 21, 1946. Mines made several flights that day, including giving Munro his first flying lesson. As they were pulling the plane out of the water a man drove down from the highway and asked if they’d be selling flight instruction. Kenmore Air had its first customer.

Kenmore Air in 1948. As you can see, the abandoned shingle mill became a thriving hub.

In addition to the mill the property featured a house with a separate garage and a small building that had apparently served as a chicken coop. Collins and his wife moved into the house, the garage became the repair shop and the chicken coop was slid over next to the garage to become the company’s headquarters.

The instruction side of the business boomed almost overnight thanks to the demand from returning GIs. The forty-horsepower Aeronca was too underpowered to be an effective trainer so the company acquired a more powerful Taylorcraft. In a pattern that would be repeated time and time again they got a deal on it because the plane was heavily damaged, but Kenmore’s skilled mechanics returned it to pristine condition in no time.

A lot happened in 1946. The company’s fleet grew by several more planes as the instruction business took off. Additional instructors and mechanics were hired. But the year also saw the departure of two of the company’s founders. Jack Mines was killed when an inadvertent stall caused him to hit the trees while airdropping supplies to a search party in the Cascade Mountains. A few months later Reg Collins announced he was moving to California. Less than a year after they’d started Bob Munro was left to run the company on his own.

Kenmore Air may have been propelled into existence by a gust of wind but it was accelerated down the road to success by a fish. For years Enos Bradner, an avid fly fisherman whose day job was being the outdoor reporter for the Seattle Times, had been hearing rumors about big steelhead trout that spawned in the rivers on Vancouver Island before speeding back to salt water to grow even bigger. In 1950 he decided to find out if the rumors were true, so he called Kenmore to arrange a charter flight. Munro had continued taking flying lessons after Jack Mine’s death and had become as accomplished a pilot as he was a mechanic. He agreed to fly Bradner and a photographer to Nahmint Lake deep in the mountains that run the length of Vancouver Island.

A successful fishing charter. Bob Munro (second from right) and the company Seabee.

He used the company’s Republic Seabee, a rugged, four-place flying boat. Republic only made the amphibious Seabee for two years but they proved remarkably popular, particularly in the Pacific Northwest, and by the late 1940s there were as many as thirty-six of them parked on the property.

After a day of fishing Bradner had confirmed two things. The rumors were true, and the Nahmint steelhead weren’t just big, they were monstrous. His described his experience in his next column and the phone in Kenmore’s little office began ringing off the hook with requests for charter fishing flights.

In early February, 1953, it rang with a charter request from Ketchikan, Alaska, that would lead to some of the most unique flights ever undertaken by any seaplane operator on the planet. The customer was a Canadian prospector named Tom McQuillan, and what he wanted was to be flown onto the surface of the Leduc Glacier in the Coast Range some eighty miles northeast of Ketchikan. He was convinced the mountains beside the glacier held massive deposits of copper and he was desperate to stake a claim before anyone else could get there. The air services in Ketchikan turned him down but someone suggested he call Bob Munro at Kenmore Air.

“He’s a hell of a pilot,” the man said. “He’s also not the kind of guy who’ll panic if something unexpected happens.”

One of Kenmore Air’s Norduyn Norsemen and the company’s Republic Seabee on during the Leduc Glacier airlift.

Munro agreed to give it a shot. Two days after his arrival in the Seabee he and company pilot Paul Garner loaded up McQuillan, his assistant and their equipment and took off for the glacier. Kenmore operated their Seabee without its external retractable landing gear, so the hull touched down smoothly on the snow-covered surface and slid to a stop. After unloading, the four men wrestled the plane around to point downhill, stomped out a short runway in front of it and Munro and Garner climbed in and took off. The flight had been a dramatic proof-of-concept that was to serve Kenmore Air well for the next two and a half decades.

With his claim staked, McQuillan’s next challenge was to establish an exploratory mine to determine if the mountains did indeed hold a treasure-trove of copper. Doing this would require a permanent camp. Wall tents, support platforms, stoves, air compressors, pneumatic drills, stacks of fuel drums, even a washing machine had to be set up on the slope above the glacier. Packing all this in would take ages so it was back on the phone to Kenmore to see if they could fly it directly onto the surface of the glacier. Munro saw no reason why not although it would take a much larger plane than the Seabee to do it.

Fortunately, Kenmore Air had two of them. The big Norduyn Norseman, nicknamed the Thunderchicken, was Canada’s first, purpose-built bush plane. Kenmore had acquired theirs in poor condition but the company’s mechanics soon had them in first-class shape.

At the beginning of March McQuillan put together a floating camp and moored it in Burroughs Bay, sixty-miles northeast of Ketchikan. From there it was a thirty-mile, continuously-climbing flight to the surface of the glacier. Using the Norsemen and the Seabee, Munro and pilots Paul Garner and Bill Fisk began flying in the tons of supplies and equipment McQuillan was having barged in from Canada. Every load was a challenge. Bundles of lumber were lashed to the float struts. A tractor had to be taken apart and the pieces flown in separately. The air tank for the compressors was too big to fit inside a Norseman, so it was torched in half with each half loaded to stick out the doors on either side.

When the weather cooperated and with the miners McQuillan had hired doing the unloading, each plane could make several flights a day. The record was thirteen, with Munro flying six and Garner five while Fisk flew two loads of food in the Seabee. The surface of the glacier took on the appearance of a ski slope from the tracks of the arriving and departing seaplanes.

The final flight was on April 29, and the planes headed south the next day. By midsummer McQuillan’s exploratory mine was in full swing. Backed by a mine development company in Vancouver, it proved the mountains held copper in amounts surpassing McQuillan’s wildest expectations. The success of the famous Granduc mine, which pulled copper out of the mountains until 1984, was the direct result of Bob Munro’s willingness to take on a challenge no one else wanted to tackle.

Kenmore Air may have thought they were done with glaciers but the glaciers weren’t done with them. In the summer of 1968 the phone rang with another request to fly equipment and supplies to a glacier. This time it was closer, the little South Cascade Glacier in the mountains a mere seventy miles northeast of Kenmore Air’s home dock.

The person on the phone was Wendell Tangborn, who’d recently been put in charge of a research station where scientists were studying the glacier’s structural zones and their behavior and how its recession might affect the region. Tangborn needed a fast and reliable way to get supplies in and data and study samples out.

Initially, the idea was to make the flights to the lake at the foot of the glacier. Using maps provided by Tangborn and the performance data for the airplanes they’d be using, Munro determined that landing and taking off from the tiny, kidney-shaped lake was possible. He also determined that once he started a takeoff he was committed to it. The lake was too small to cut the power and stop once the plane was into its takeoff run.

The two Thunderchickens had been sold off years earlier. Two years before Tangborn’s phone call, Kenmore had purchased its first de Havilland Beaver. Like the Norseman, the Beaver had been designed specifically for the Canadian bush. But instead of the Norseman’s heavy tube-and-fabric construction and truck-like handling, the Beaver utilizes lightweight, all-metal construction and it flies like a dream.

The Beaver quickly came to define Kenmore Air. The company began acquiring more of them, many as Army surplus hulks. But Kenmore’s wizard mechanics turned the hulks into planes that were better than even de Havilland could have imagined. Under the guidance of service manager Jerry Rader, they increased the cabin capacity, created more comfortable seats and installed bigger windows to give passengers an even better view of the amazing geography they were flying over. The end result was what operators around the world began referring to as a Kenmore Beaver.

Munro’s first flight to the tiny lake was a success and for the rest of the summer Kenmore made at least one flight a week in support of the station. Then in October the lake froze over. The surface of the South Cascade was too uneven to land on in the summer but once the snow began to fall it was a different story. Drawing on everything he’d learned during the Leduc airlift, Munro took his favorite Beaver, N9766Z, and went up and tried it. It worked and Tangborn’s research projects could now carry on through the winter.

As dramatic as the glacier flights were, they made up just a fraction of the company’s income. The charter business had grown to include daily flights to the resorts scattered through the maze of islands that make up the lower British Columbia coast. Stops included April Point, Farewell Harbor, and Big Bay, where guides took guests out to fish the edges of the huge whirlpools that form in the narrow passes between the islands. The violent water churns up food which attracts schools of herring which in turn launched trophy-sized salmon into a feeding frenzy.

Kenmore’s growing fleet of immaculate Beavers might have been the public’s image of the company but there was a lot more to it than that. The maintenance and repair side of the business had evolved right along with the company’s airplanes. In the beginning, while Jack Mines was out giving lessons, Collins and Munro would be hard at it in the garage rebuilding engines or fixing components of customers’ planes.

Kenmore Air’s first Turbo Beaver. (photo by C. Marin Faure)

In 1961 the original house, garage and chicken-coop office were knocked down and a pile driver began hammering in the supports for a combination office and hangar building. Designed and largely built single-handedly by Kenmore’s genius facilities manager, Bill Peters, the building still stands today as the company’s headquarters.

Word spreads fast in the northwest aviation community and it wasn’t long before Kenmore’s Beaver-rebuild mechanics found themselves putting together planes for operators in Alaska, Canada and even overseas. Winters began seeing planes in the hangar with names like Alaska Island Air, Taquan Air Service and Pacific Wings on their sides, flown south for an off-season overhaul.

In the spring of 1970 one of Seattle’s newspapers ran an article about Kenmore Air’s South Cascade Glacier operations. That same afternoon Munro got a call inquiring if he’d be willing to do the same thing for the University of Washington’s research station on the Blue Glacier. Spilling off the summit of Mt. Olympus on the Olympic Peninsula far from Seattle’s automotive and industrial haze, the Blue was an ideal place to study weather, air chemistry, and cloud physics as well as the glacier itself. The station was perched on a ridge beside the rounded upper level of the glacier. Nicknamed the Snow Dome, it was flat enough to land on.

Munro pored over the maps and photos the university had provided. The Snow Dome was definitely long enough to land on. But was it long enough to take off from? According to the map and the Beaver’s performance figures it wasn’t. Not even close.

But Munro’s examination of the photos showed him something the maps didn’t. A narrow extension of the Snow Dome continued past the research station and spilled off the mountain in a smooth curve of ice to dive steeply into the valley below.

The only way to find out if his idea would work was to go up and try it. Compared to the South Cascade, landing on the Blue was a snap. The two researchers who’d accompanied him helped turn the Beaver around and then climbed back in and tightened their seat belts as Munro advanced the throttle to takeoff power. The plane began to accelerate but it was obvious it would never reach flying speed before it reached the end of the Snow Dome. But Munro held his nerve and kept going. Six-Six-Zulu was still way too slow when it reached the end and pitched over the edge. It was like a roller coaster, Munro said later. The plane picked up speed fast as it thundered down the slope until at an angle approaching forty-five degrees it reached flying speed. Munro eased back on the yoke and 66Z lifted off the snow and rocketed toward the floor of the valley. Resisting the urge to pull back too hard, Munro coaxed the plane out of its dive and headed for home.

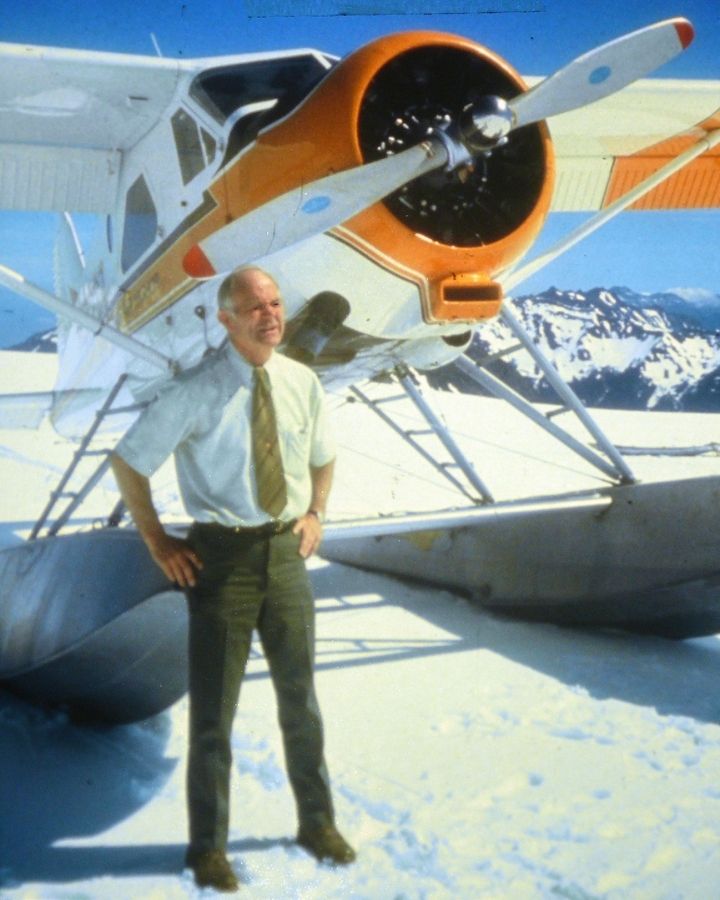

Bob Munro with his beloved Six-Six-Zulu poses after a glacier landing.

Kenmore Air supported the Blue Glacier station for the next seven years, ferrying everything from drums of stove oil to sensitive research instruments to the Snow Dome and hauling away the station’s empty containers and trash. And while the flights themselves became relatively routine, the dramatic pitch over the icefall on takeoff never ceased to be a thrill.

Lake Union Air Service had been around almost as long as Kenmore Air, and in the early 80s a new owner decided to make it a serious contender by starting scheduled service to the most popular destinations in the San Juan Islands. Kenmore met the challenge by starting its own scheduled service, which meant that passengers could now get to and from the islands by simply buying a ticket rather than chartering an entire plane. The service was an immediate success and it was soon expanded to include destinations farther north in British Columbia.

Both companies began to struggle as the competition heated up. Something had to give and it did in 1991 when the over-extended Lake Union company found itself descending toward bankruptcy. Munro could have waited until his competitor failed altogether, but instead he made the owner a fair offer and Kenmore took over the company’s Lake Union facility as well as its lucrative route to Victoria on Vancouver Island.

Kenmore Air entered the jet age in 1986 with the acquisition of a de Havilland Turbo Beaver. With a longer fuselage and a turbine in place of the standard Beaver’s piston engine, the Turbo Beaver carries more, goes faster and has significantly longer maintenance intervals. Kenmore got a good deal on theirs because someone had run it into the side of a truck and wiped out the front end. Which was fine because Jerry Rader’s plan was to replace the original 1960s-era turbine with a brand new, more powerful version that was better suited for saltwater operations. Kenmore’s Beaver shop totally rebuilt the plane and it joined the fleet in 1988. A major benefit became obvious on its very first flight. The turbine, with its large, slower-turning propeller, was noticeably quieter than the fleet’s piston-powered planes. A year later, the company added a second re-powered Turbo Beaver.

The success of the Turbo Beavers convinced Munro to approve the conversion of Kenmore’s largest plane, a ten-passenger de Havilland Otter, from piston to turbine power. Using an FAA-approved conversion kit that incorporated the same state-of-the-art turbine Rader had used in the Turbo Beavers, the end result was a plane that matched Kenmore’s needs perfectly. Today, the fleet includes ten of them.

Fifty-four years after the flight that launched Kenmore Air, Bob Munro retired. His son, Gregg, became president of the company while grandson Todd Banks took over the day-to-day operations. When Seattle-based Horizon Air ended its scheduled service to Port Angeles on the Olympic Peninsula, Banks saw an opportunity with potential. Using nine-passenger Cessna Caravans on schedules tied into the most popular arrival and departure times at Seatac International Airport, Kenmore Express began offering scheduled and charter flights between Seattle’s Boeing Field and airports on the Peninsula, in the San Juan Islands and in British Columbia.

Turbine Otter at Kenmore’s home dock. (photo by C. Marin Faure)

The enthusiastic reaction of passengers as they try to take in every detail of the maze of inlets, bays and islands passing below them did not go unnoticed by Kenmore’s pilots. Remembering his grandfather’s fascination for the country he’d flown through for so many years, Banks wondered if people would be willing to pay for the experience of simply going for a ride in a floatplane. The only way to find out was to try it, so the company initiated a sightseeing flight over Seattle. It proved so popular that Kenmore added a volcano flight that gets passengers up close and personal with Mt. Rainier and Mt. Saint Helens, and an Olympic Peninsula flight that includes a pass over Mt. Olympus and the Blue Glacier. Depending on the day’s fleet assignments, passengers may find themselves gazing down on the Snow Dome from Beaver Six-Six-Zulu, the exact same plane Munro flew on his South Cascade and Blue Glacier flights.

The magic of flying in a floatplane is you go low and slow. With big windows and a high wing, every seat offers a panoramic view. Which is exactly what you want as you look down into the steaming crater of Saint Helens or watch a pod of whales from the altitude of a soaring eagle.

Whether the objective is to experience a unique perspective above an amazing corner of the planet, add to a collection of dramatic photos and videos, or fly to a destination with its own promise of adventure, Kenmore Air has spent the last seventy-five years perfecting its ability to deliver. It’s a history every passenger lives in person from the moment their plane begins to accelerate across the water.

About the Author

C. Marin Faure was born in San Francisco, California and grew up in Honolulu, Hawaii. After graduating from the University of Hawaii he worked in commercial television production for eight years before moving to Seattle, Washington and joining The Boeing Company as a marketing film and video producer/director, a job that has taken him all over the world.

In Hawaii he earned his Commercial pilot’s license with Instrument and Flight Instructor ratings. After moving to Washington, he earned his seaplane rating and with his wife, Ruth,has made numerous camping and fishing flights in a float-equipped de Havilland Beaver up and down the Inside Passage between Washington and southeast Alaska. They’ve also explored the waters of Washington and British Columbia extensively by boat.

Marin began writing articles about flying floatplanes for national flying magazines and in 1984 was asked to write an instructional book on the subject. The first edition of “Flying a Floatplane” (274 pages) was published by TAB Books (McGraw-Hill) in 1985. Subsequent published books include “Success on the Step: Flying with Kenmore Air” (432 pages, foreword by Harrison Ford), the story of the world’s most successful seaplane airline, and “Up From the Ashes: The Clise Family and the Shaping of Seattle” (231 pages), the story of Seattle’s most influential and successful family-owned property development company.

Marin’s beautifully written Success on the Step – Flying with Kenmore Air is available through our online Gift Shop

Celebrate Kenmore’s 75th!

In honor of our 75th anniversary, we’d like to extend a warm welcome to the entire community. Please join us in celebrating August 28th, 2021 at Kenmore Air Harbor in Kenmore, WA.